Understanding reflux in babies and newborns

In this article:

- Feeding and 'spitting up'

- What causes reflux in babies?

- What is GORD?

- Why is reflux in babies a problem?

- How to identify baby reflux symptoms

- How is reflux in babies diagnosed?

- When does a baby's vomiting require urgent attention?

- What baby reflux treatment options are available?

- What is the long-term outlook for babies with reflux?

- Sources

- Main Points

Feeding and ‘spitting up’

One of the most time consuming and, at times, challenging aspects of having a newborn baby is feeding. One associated issue is vomiting, or “spitting up” milk, and many parents are concerned that their baby has reflux and want treatment for it. Nearly half of all babies will have some degree of reflux, but most don’t actually need treatment. So what is reflux and how can it be managed?

What causes reflux in babies?

The first aspect to understanding reflux is to understand the difference between the structure of the feeding pipe (oesophagus) and stomach in a baby compared to older children and adults. Once fully matured and developed, there is a muscular tightening at the bottom of the oesophagus where it passes into the stomach (lower oesophageal sphincter) this helps to prevent food entering the stomach from coming back up again. In newborn babies, this is not fully developed and so it is easier for milk from the stomach to go in the wrong direction and come back up. Combine this with the fact that babies spend a lot of time lying flat while asleep, and due to their small size there is a shorter distance for milk to travel to come back up, and you can see why reflux can be a problem in newborn babies.

You may have also heard the term acid reflux, rather than just reflux. Part of the role of the stomach is to add acid to anything ingested to help break it down for digestion and also to kill off and protect the body from bugs that might potentially cause infection. The lining of the stomach is especially adapted to be able to cope with the acid, but the oesophagus and back of the mouth aren’t (you’ve probably all experienced the burning that comes after vomiting). Some babies will reflux mostly milk and little discomfort is caused. However, if it’s very acidic, this can cause more problems.

What is GORD?

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is the term used to describe the more severe end of the spectrum of reflux, whereby the baby’s growth and development are being affected or the baby is experiencing significant problems as a result of reflux (see below) and they usually need treatment.

Babies who have other significant medical problems, especially if they are premature or have neurological or development problems, are more likely to be affected by reflux. These babies are also more likely to need treatment for this problem.

Why is reflux in babies a problem?

Reflux becomes a problem when the amount of milk coming up is significant enough to prevent a baby’s nutritional needs from being met fully and they start to struggle to grow (often known as ‘failure to thrive’ in babies, reflux is just one of many causes of this).

When the milk that is refluxing is more acidic this can cause discomfort for babies, leading to babies who are very unsettled with or just after feeds. This can sometimes lead to feed aversion where babies refuse to take feed because they are trying to avoid the associated pain. This can further impact growth problems. If very severe, the acid can cause damage to the oesophagus leading to irritation of the lining (reflux oesophagitis). Babies with severe reflux are more prone to ear infections (otitis media) and, very occasionally, when milk comes back up, some milk can go ‘down the wrong way’ into the lungs and cause problems such as chest infections and breathing difficulties (aspiration pneumonia).

How to identify baby reflux symptoms

Reflux causes a spectrum of problems and babies can be mildly affected or severely affected.

Generally, posseting occurs when just a small mouthful or teaspoon volume of milk comes back up. Such babies are otherwise doing well, growing and developing well. This is completely normal and on its own posseting is not a concern.

Significant reflux will therefore generally involve larger volumes of milk or vomit, often soaking babygros and sheets. The vomiting will also be affected by position: babies that have reflux will have more significant symptoms when they are laid flat after feeding, and fewer symptoms when held upright. Typically, the vomiting will happen immediately or shortly after feeding. Vomiting which occurs hours later is unlikely to be related to reflux.

One of the biggest concerns parents have when wondering if their baby has reflux is excessive crying and although this does occur in reflux, particularly at or around the time of feeding, there are also many other reasons for long periods of crying in babies. Significant proportions of completely normal, healthy babies will cry for extended periods of time daily and, although this can be distressing and exhausting for new parents, it does not necessarily indicate the diagnosis of reflux.

Other slightly more specific signs of distress in reflux include back arching during or after a feed.

The most important sign of reflux, signifying that treatment is probably required, is when there is an impact on your baby’s growth and development. It’s important to get your baby weighed regularly, which you can easily do at your local Health Visitor clinic or GP and they will plot this information in your baby’s red book to check they’re growing along the same centile line.

You may have come across the term ‘silent reflux’ and parents often worry that their baby may not have the classic signs of vomiting so the diagnosis is being missed. This is unusual and in such cases the important differentiator will be the growth of the baby as described above.

How is reflux in babies diagnosed?

Reflux is usually what we call a ‘clinical diagnosis’ which means that typically it is made after hearing parents describe their babies behaviour and feeding, and by examining the baby for any signs of growth or developmental problems. Sometimes, another ‘investigation’ will be to trial treatment and see if it helps. A marked improvement in symptoms when starting medication will help confirm the diagnosis. Occasionally, in cases that are unclear and severe, particularly if surgery is likely to be the treatment (see below), a test called a pH study might be performed.

A pH study involves your baby having a small tube passed down to the bottom of the oesophagus to measure the acidity (pH) of the contents and then to see if any contents from the stomach are coming back up. It will usually be conducted in a hospital and the tube will stay in place for a set period of time.

When does a baby’s vomiting require urgent attention?

Occasionally, there might be another cause of vomiting and in some cases this might require urgent investigation and other treatment. It is important to seek urgent medical advice if your baby has any of the following:

- Frequent, forceful (projectile) vomiting where the vomit is so forceful it lands far away

- Green or yellow-green vomit

- Chronic diarrhoea

- Distended or hard tummy

- Blood in vomit or poo

- If the symptoms of reflux begin after six months or persist beyond one year-of-age

- Generally unwell with fever, lethargy, irritability or bulging fontanelle

If you’re unsure, your GP or health visitor will always be happy to see your baby and give reassurance if needed.

What baby reflux treatment options are available?

In formula-fed babies who are growing well, persistent vomiting can be associated with overfeeding. Babies will often take more milk than they can manage and bring up some of the excess. Trialling smaller volumes of milk can help to reduce vomiting and mild reflux.

If there isn’t a suggestion of overfeeding, introducing smaller feed amounts more often can be successful, so that the total amount of milk in a day stays the same. Your health visitor or GP can help you work out the appropriate feed volume for your baby’s age and weight. Breastfed babies are unlikely to overfeed but, similarly, trialling shorter feeds more often may help to reduce the amount of milk coming back up.

Although there is some evidence that reflux symptoms are improved by putting the baby in different positions, such as on their front to sleep, this is not safe because it increases the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Keeping your baby upright immediately after a feed and well winded may help to reduce the amount of milk brought up.

If your baby is formula fed, your doctor may recommend a thickened formula such as one containing rice or cornstarch. The next step is to consider medication, but it is important to note that there is little evidence of this being effective and there are side effects to consider. The first type of medication is an alginate such as Gaviscon. This works by forming a protective layer over the contents of the stomach to reduce the chance of it refluxing back up. The main issue with this medication is that it often causes constipation in babies.

The next group of medications act to reduce the amount of acid produced in the stomach and examples of these are omeprazole and ranitidine. By reducing the amount of acid, they reduce the chance of discomfort by making the milk less acidic but, importantly, they do not prevent the mechanism of the reflux itself. One other consideration when using these medications is that, by altering the acidity of the stomach, they can affect the normal gut flora (the good bacteria that help to protect your gut against infections) and there is an association with an increase in gastrointestinal infections.

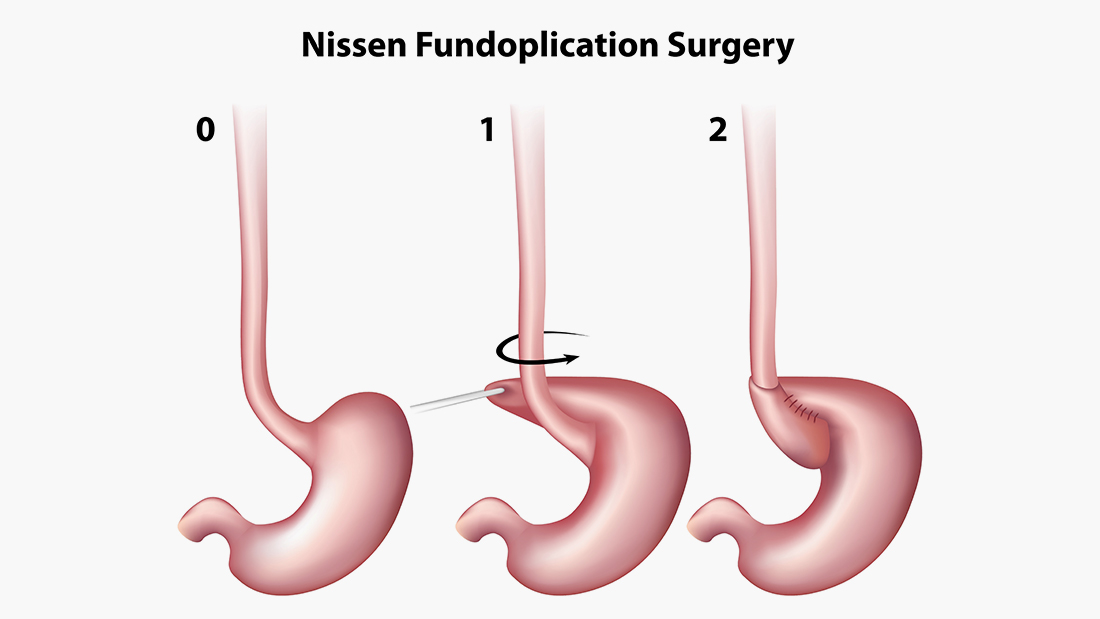

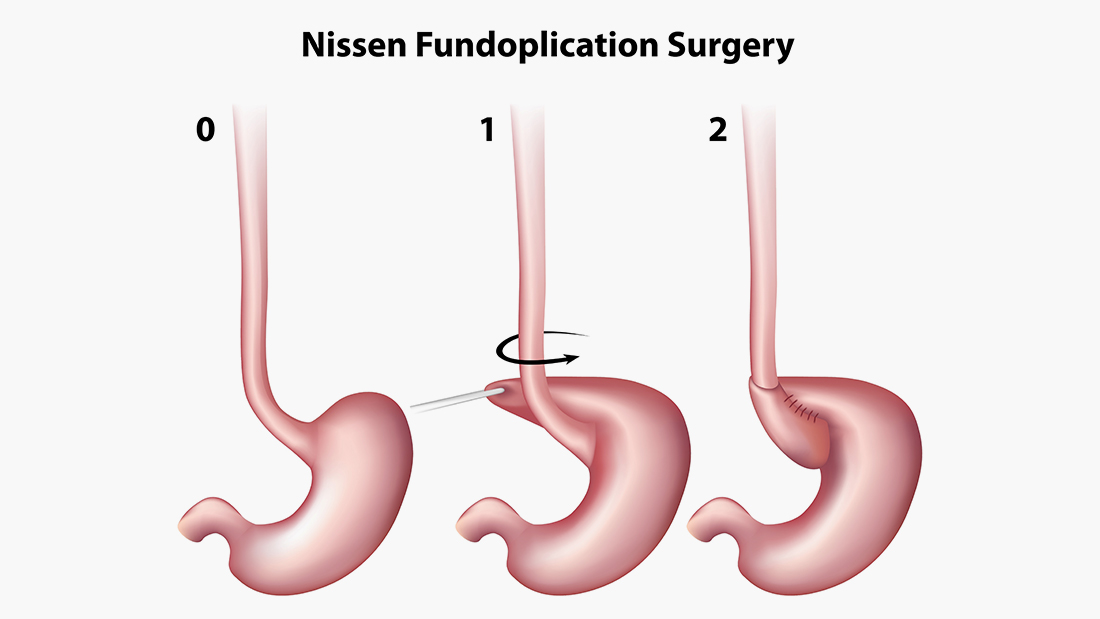

In really rare, severe cases of reflux, that are not responding to medication, surgery may be considered. This procedure is called a fundoplication and involves artificially tightening the join between the oesophagus and the stomach using another section of the bowel. Sometimes, at the same time, a feeding tube will be inserted into the stomach or further down the bowel.

What is the long-term outlook for babies with reflux?

The key thing with reflux is that, due to it being related to positioning and the immaturity of the gut, nearly all babies grow out of it. As the join between the stomach and oesophagus becomes stronger and babies spend more time upright as they learn to sit up and sleep less, the symptoms become less pronounced and, in most cases, go away completely before a baby becomes turns one.

Solid food is also much harder to bring up, so around the time of weaning symptoms are also likely to reduce. This means it is important to intermittently try stopping any medications being trialled to see if symptoms have resolved.

Sometimes, improvements are actually due to babies growing out of the reflux rather than the medications having worked. This also helps to ensure any side effects are experienced for as short a time as possible.

Sources

NICE guidelines

Cochrane review: Medicines for children with gastro-oesophageal reflux

Main Points

- Reflux in babies primarily occurs because the lower oesophageal sphincter is not fully developed, making it easier for the stomach contents to rise back up.

- Almost 50% of babies will have some level of reflux, but most will not require treatment and nearly all babies grow out of it.

- Bottle fed babies often take on more milk then they can manage and trying smaller volumes of milk more often may help to reduce vomiting and mild reflux.

- The condition is typically diagnosed following parents’ description of baby’s feeding and behaviour, and examining the baby for specific growth or developmental problems.

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD) describes the more severe end of the scale of the condition. This is when reflux has an impact on a baby’s growth and development or the baby experiences other major problems.

- Symptoms such as frequent projectile vomiting, green or yellow-green vomit, chronic diarrhoea, a distended or hard tummy, or blood in vomit or poo could require further investigation and treatment.

- More severe cases of reflux can also lead to ear infections, chest infections or breathing difficulties.

- There is little evidence of medication being effective for reflux and a type of surgery, fundoplication, may be considered in severe cases of the condition.

- Medications which reduce the amount of acid in a baby’s stomach, while reducing discomfort, can impact the normal flora within the gut which protects the gut from infection. They also do not stop the mechanism of reflux itself.

- An alginate medication such as Gaviscon prevents reflux by forming a protective layer in a baby’s stomach. However, it is also known to cause constipation.